The Monstrous Beloved and the Sovereign Feminine

A mythic descent into feminine power, shadow desire, and the ritual of being chosen whole—where reverence breaks curses and the grotesque becomes sacred.

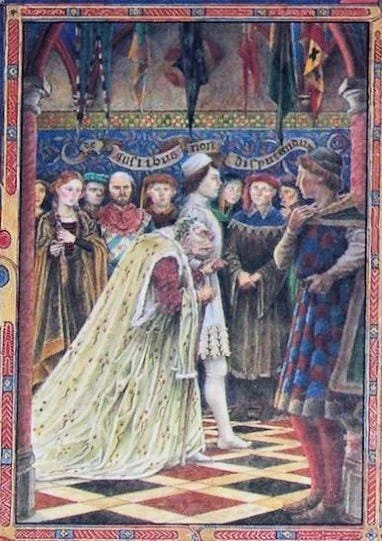

Illustration by Juan Wijngaard for the book: Sir Gawain and the Loathly Lady by Selina Shirley Hastings (1985)

The Riddle and the Bride

It begins, as so many tales do, with a man in the woods and a question he cannot answer. King Arthur, proud and weary, finds himself alone and vulnerable, separated from his knights, his crown heavy with the weight of rule. A mysterious knight named Sir Gromer Somer Joure challenges him to a duel and demands an answer to a riddle within one year:

What do women most desire?

If King Arthur fails, he will lose his life. The question haunts him. He asks queens and crones, maidens and mothers, but no answer satisfies. As the deadline looms, King Arthur is desperate.

And it is then, in the shadowed margins of the court, that Lady Ragnell appears, grotesque, commanding, and holding the answer he seeks. Her face is twisted, her body misshapen, her voice sharp with knowing. She offers the solution, but only if Sir Gawain, the noblest knight, takes her as his bride. Sir Gawain, ever loyal, consents. And so the wedding is held, and the court whispers behind veils and goblets, wondering what madness had possessed him.

But on their wedding night, Lady Ragnell offers Sir Gawain a second riddle: Would he prefer her beautiful by day, when others could see her, or by night, when she lay beside him?

Sir Gawain does not choose.

Instead he says, You choose.

And in that moment, something ancient breaks open. The curse lifts. Lady Ragnell transforms, not just in body, but in fate. Her sovereignty is restored, and with it, her beauty - day and night.

The answer to the riddle was not youth, nor obedience, nor beauty. It was sovereignty. What women want is the right to choose for themselves. And this answer, offered through myth, ritual, and erotic exchange is more than a plot twist. It is a spell for cultural healing.

This riddle is a spell because it names what has long been denied:

feminine sovereignty.

Spoken in a moment of crisis, it becomes a ritual act that reshapes reality. The curse isn’t lifted by cleverness or violence, it’s broken by reverence, by erotic surrender to the beloved’s agency. Sir Gawain’s “You choose“ is more than consent, it’s a mirror of relational repair, a model for how love can become a vessel for healing.

Culturally, the riddle exposes the wound at the heart of patriarchal systems: the fear of feminine autonomy. It reclaims the monstrous feminine not as a threat, but as sacred. It reminds us that sovereignty is not selfishness, it is soulhood. In a time when women’s rights are under siege, this ancient tale becomes a mythic map. To honor a woman’s choice is to restore balance. To adore her wholeness is to break the curse.

Lady Ragnell doesn’t just want a husband. She wants Sir Gawain, the golden knight, the paragon of chivalry, the one whose name carries weight in both court and myth. He is the best of the best, the one closest to King Arthur, and the only knight whose loyalty and honor would compel him to marry a grotesque stranger to save his king. Lady Ragnell chooses the one who will choose her. This isn’t just a marriage, it’s a ritual exchange. Lady Ragnell offers the answer that saves King Arthur’s life. In return, she claims a union that restores her own sovereignty. Sir Gawain, as the most prized knight, becomes the vessel for that restoration.

This tale, centuries old, pulses with relevance now. As Halloween approaches, we flirt with monsters and masks, but beneath the costume lies a deeper truth. We are living through a time when women’s rights, bodily autonomy, and erotic agency are under siege. The question of sovereignty is not abstract, it is urgent.

Lady Ragnell’s story reminds us that the monstrous feminine is not to be feared, but revered. Beauty is not about compliance, but about choice. And that love—true love—is not passive acceptance, but active adoration of the whole self. In the genre of monster romance, this ancient truth finds new life. The grotesque becomes sacred. The shadow becomes beloved. And the answer to the riddle becomes a spell for cultural healing.

Illustration by Juan Wijngaard for the book: Sir Gawain and the Loathly Lady by Selina Shirley Hastings (1985)

Lady Ragnell as Proto-Monster Romance Heroine

Lady Ragnell’s hideous form is more than a curse, it’s a mirror. Her grotesque visage reflects the fears the patriarchal gaze cannot tolerate, acknowledge, or hold space for: feminine autonomy, erotic agency, emotional intensity, and the refusal to be palatable. Lady Ragnell is not a mere victim of enchantment; she is what the masculine sees as the incarnation of what happens when the feminine refuses to shrink.

We’d be mistaken to take her demand for marriage as a plea. Lady Ragnell doesn’t just want a husband; she wants a ritual partner. She chooses Sir Gawain not for his status alone, but because of all the knights in King Arthur’s court, he is the one whose loyalty is embodied, whose honor is relational, whose love is a verb. She chooses Sir Gawain because he is the one most likely to choose her—not out of pity, but out of devotion to something bigger than himself and appearances. His character is the only one in King Arthur’s court who would marry a grotesque stranger without protest, without revulsion, without trying to bargain her down. She selects the knight whose love will be active, not passive.

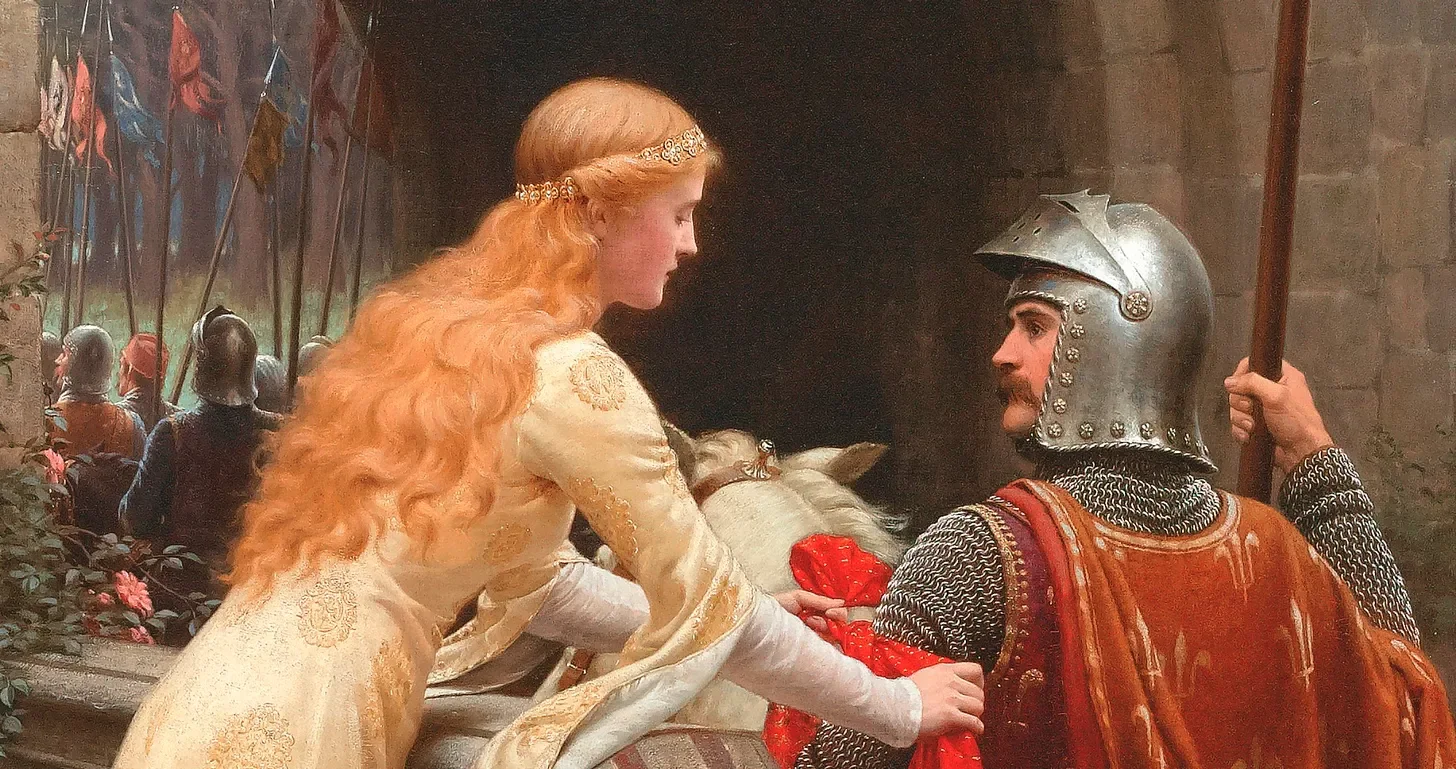

When Sir Gawain utters “You choose,” it is not a passive gesture. He doesn’t claim Lady Ragnell’s beauty for himself or for appearances’ sake. He honors her right to decide how she will be seen, when, and by whom. In doing so, he transforms the marriage from a transactional bargain into a sacred exchange. His ability to acknowledge her autonomy lays the foundation for love as a vessel for sovereignty, not a cage. These simple two words “You choose“ reveal how Sir Gawain exemplifies active reverence, not given meekly through silence or submission.

The hinge moment when he says “You choose” is not passive consent,

uttered in dismissive boredom, as so many men have done to women

(“Whatever you want, dear”).

Those two words, spoken by the most respected knight in the kingdom, become an erotic adoration of feminine power. Sir Gawain doesn’t just respect her autonomy, he eroticizes it. In that moment, Lady Ragnell is not merely accepted; she is adored. And adoration, in its original sense (adorare: to worship), is active, reverent, and relational. It is the erotic elevation of the beloved’s agency. In this light, Lady Ragnell becomes the ancestral blueprint for the monster romance heroine: feared, misjudged, and ultimately loved into sovereignty.

The Vigil by John Pettie (1884) - Sir Gawain represented as the perfect knight, lover and religious devotee.

Monster Romance and Erotic Agency

In modern monster romance, the heroine falls not for the monster’s danger, but for his devotion. The monstrous beloved be he demon, dragon, alien, or beast is not a threat to her autonomy, but a mirror for it. He does not tame her; he witnesses her. He does not fix her; he reveres her. His monstrosity becomes a container for her shadowed desires: her rage, her grief, her hunger.

This is not a story of domination, it’s a story of surrender, not to the monster, but to the self.

The heroine’s erotic power is not feared or punished; it is cherished. The monster does not merely accept her complexity; he adores it. And in that adoration, something ancient is healed.

Monster romance, as I’ve been reflecting on, doesn’t just entertain, it initiates. It makes the heroine’s agency the site of intimacy. The love she receives is not passive, it is active reverence. The monster doesn’t just tolerate her shadow, he loves through it. And in that love, the curse that’s been holding the heroine’s power prisoner breaks.

This is the kind of love that monster romance dares to imagine: not a taming, but a witnessing. Not a rescue, but a recognition. It’s the kind of love that meets the heroine in her fullness and says, I see you. I choose you. And in that choosing, something mythic stirs. The grotesque becomes sacred. The shadow becomes beloved. And the heroine, at last, becomes sovereign.

God Speed! - Edmund Blair Leighton (1900)

Monster Romance as Mythic Medicine for Our Times

Monster romance, in this light, becomes mythic medicine: a genre where the grotesque is sacred, the shadow is loved, and the beloved is adored. But if Lady Ragnell is the ancestral heroine: sovereign, shadowed, and chosen, then what of the monsters themselves? What do they carry?

This is the question at the heart of the next descent. Because monsters are not just symbols of danger or desire: they are vessels. They hold the wounds of the masculine—the grief, shame, and distortion born of centuries of toxic power. They carry the parts of the feminine that patriarchy could not accept: rage, emotional intensity, hunger, desire. These qualities were cast out, projected onto monsters, and punished in women. And yet, the monsters remain. They become vessels not only for the masculine’s healing, but for the feminine’s reclamation.

They hold what was denied expression: the sacred fury, the erotic appetite, the grief that demands to be witnessed. They do not retaliate. They do not devour. They hold. They wait. They love through the shadow.

In this four-part series—What Women Want: Monsters, Sovereignty, and the Erotic Return of the Repressed—we’re not just tracing tropes. We’re mapping a mythic journey. From the riddle of sovereignty to the erotic reunion with shadow, from monstrous devotion to cultural healing, each article becomes a ritual act. A way to read not just for pleasure, but for transformation.

At the heart of this descent is the monster himself, centered as a container for both projected and repressed energies, a kind of mythic therapist, lover, and witness rolled into one. In the coming articles, we’ll explore how these monsters hold the grief of the masculine, the rage of the feminine, and the shadow desires that culture has long refused to name.

May the Power of Fluff be with you.

Vanessa Couto