Good Daughters Don't Have Fangs*

Mine Grew Back After My Mother Died

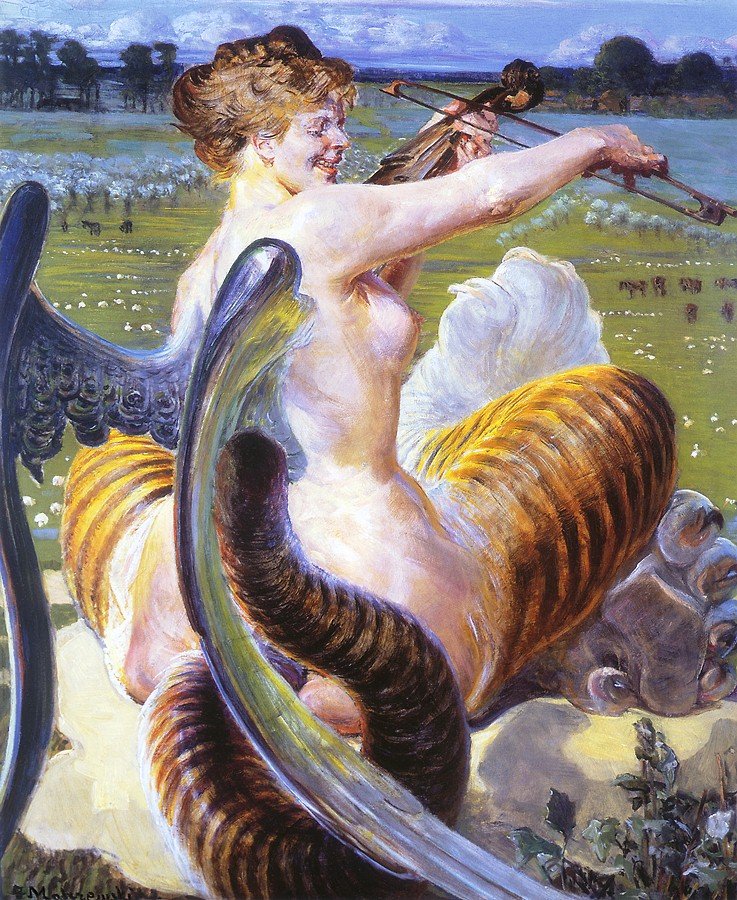

The Artist and The Chimera (1906) - Jacek Malczewski

*When I announced this article as “Monstrous Devotion and Erotic Sovereignty,” I thought I’d write theory. But the monsters had other plans—they wanted testimony. What follows is how they brought me back to life.

My mother died exactly a year ago—a gift in more ways than one. Mainly because the monsters were waiting to meet the return of my hunger.

I need to tell you this because every attempt to write this article felt flaccid as I was trying to write about the tooth-and-claw of monsters from a safe academic distance. Not until I realized that I needed to face within myself that the truth is messier.

My grief journey after my mother’s death has been so different than I feared or expected it would be.

The gift of her death was breaking me free from many of the chains that kept me in ‘good daughter’ mode, leaking away vital libido force from me.

The ‘good daughter’ who tried so hard to fit into her unspoken demands, hiding my joy so as to not upset or raise her snappy petty jealousy, doing the impossible quadrille steps in a dance between showing up for her while protectively hiding what was sacred to me from her envious anger.

Dido Mourns with Aeneas’s Sword Before Her (1493)

Unlike the grief journey of my father’s death, filled with sadness, a meandering loss, with many afternoons of tea and scones with Lady Grievana (Grief personified by Helen Mirren in my imagination), my grief journey for my mother has been filled with anger and an urgent need to live life’s delights and pleasures, because seeing the rawness of death waiting for my mother by her bedside slapped me awake.

Granted this is still a work-in-progress, where my old ‘good daughter’ self flickers in and out, while the new me is still clawing through the blood-and-goo-covered canal of my own womb, I recognize the potency of this gift once desire started pouring back in, and that the only things big enough to hold this raging rebirth are creatures with tentacles and fangs.

The Nightmare (1790-1791) - Henry Fuseli

Stubbornly determined to write this article, I could only put pen to paper once I crouched down to what got me here in the first place: looking at why I crave the monster in my stories. Why the lich’s undead tendrils that sense my rage, make me lean into its caress instead of run. Why the ferocity of the scaly snake monster, who is both protective and ravenous, is more compelling than a Bridgerton Regency Duke in his cravat.

Rational explanations make all of this sound like escapist madness, or dangerously close to the need for an intervention, as a friend recently asked me if that might be my case.

I don’t need an intervention! I need others to join me in the cave!

Despite the judgments—internal and external—I’m choosing to trust the visceral power of the monster as a threshold guide in this liminal time of my life. Add the volcanic hormonal fluctuations of perimenopause and I have a Molotov cocktail a spark away just under my skin. But the monster doesn’t want to fix me any more than I want to fix it. It wants to taste all of me, licking me whole. And this knowing ignites something in me that I have been waiting for my entire life: to be taken whole—not pinched and trimmed into something palatable for the sake of hiding from my mother’s envy.

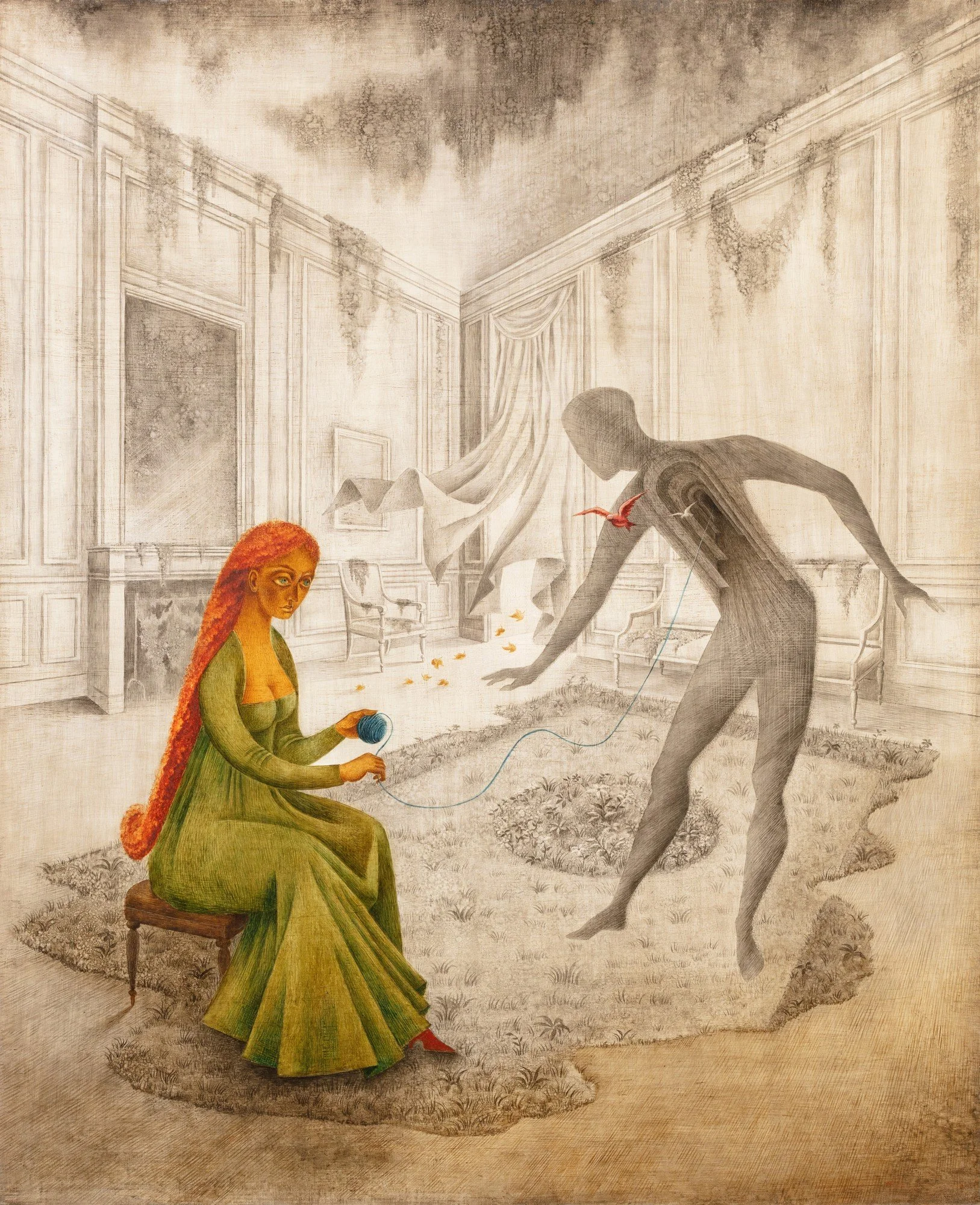

Les Feuilles mortes (Les Heures mortes) (1956) - Remedios Varo

Good daughters are damned. Good daughters are saved by monster lovers.

This is what I’ve been trying to articulate in this monster series and through launching The Healing Power of Fluff: after a year in this grief journey, reading monster romance after monster romance, I understand that these stories work because they know what sensible polite grief narratives won’t admit—that death and desire live in the same dark cave.

That sometimes losing someone who took up so much of my life force means that force comes roaring back with nowhere to go but into my own body. Renewed libido, angry impatience, zero tolerance for what doesn’t light me up - an astounding reduction in my quota of ‘fucks to give.’

Monsters are the real ‘truth tellers,’ to use the catchy, and often preachy expression of our time. They are because monsters see what we refuse or are too embarrassed to see. It’s more than just our shadows they see, it’s our appetite. To them, our appetite, in all its forms, isn’t shameful—it’s desire’s intelligence expressed.

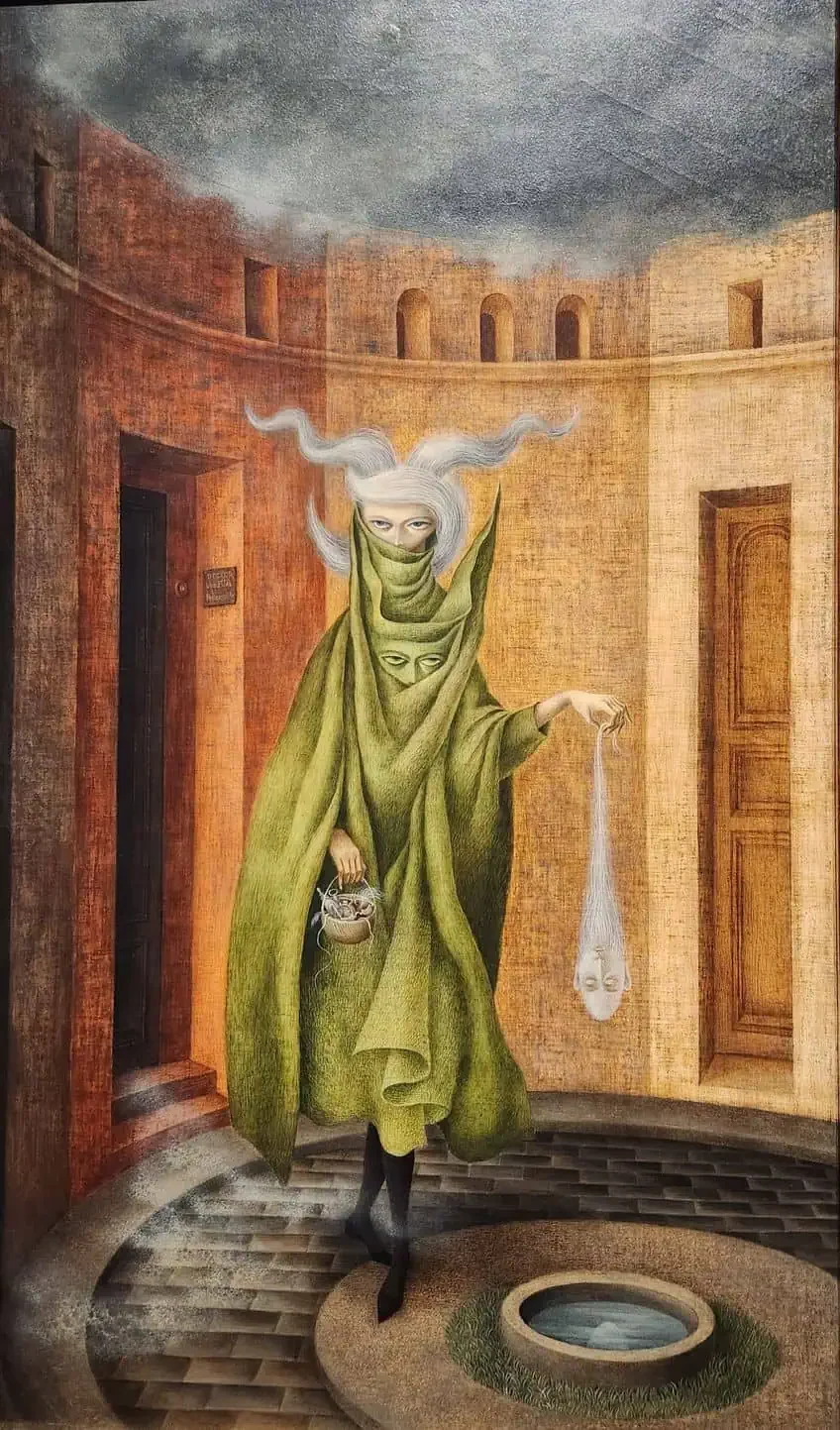

Woman Leaving the Psychoanalyst (1960) - Remedios Varo

They know by scent what therapy takes years to uncover: that the path back to life runs through the arousal of the body’s delights and desires, not around it. They show us that honest want is truer than performative virtue. They laugh at our rational mind’s clumsy attempts at hiding our raw hunger for they can smell the wet stickiness of our fears and arousal.

Beauty and her Beast. Persephone and her Lord of Bones. Even Lizzie Bennet and her proud Lord of Pemberley, the monster in a cravat, are all expressions of an archetype that stays constant in its unapologetic veracity of what it wants.

The truer stories are the ones where the beast doesn’t transform back into a handsome prince.

It’s best when he stays monstrous, and the heroine learns to see that as the point, because the alchemy isn’t about making him safe and proper; it’s about finding something dangerous enough to match her own hidden fangs and claws.

I’m still undressing the encrusted layers around my embarrassment about my appetite for these spicy novels. As if craving stories where women get eaten and like it was betraying my degrees, how I thought my grief should look, and my former self who dismissed romance as beneath-me-fluff.

This dismissal and embarrassment isn’t just personal, it’s also cultural, and it is a slow peeling off layers of petticoats in this strip-tease because it’s so pervasively ingrained. But the monsters don’t care about any leftover embarrassment about being lit up by these stories, or my resume. They care that I can finally welcome my libido back into my body, and life. Because after being drained out of me, albeit slowly, but consistently, this zest for life has returned and I thank the monsters for being both my catalysts and guides.

Allegro - Jacek Malczewski

To me this is erotic sovereignty: the moment you stop explaining your desires (away) and start feeding them.

No more “I’m sorry”, but “More, please!”

When you realize that worship, as in its true meaning of ‘to honor’ without taming, isn’t just how monsters love—it’s how we need to love the exiled parts of ourselves—the parts that got matted wild hair and grew scabby scales in the dark.

The parts that know pleasure is its own sovereign, not a consolation prize for being deemed good.

The academic voice still grips, wanting distance and theory. But I’m prying my Gemini mind’s fingers loose, letting my Taurean body speak, my Pisces moon weave the mythic threads. This is my strip-tease—clumsy, necessary, mine.

I know respectability is exactly what kills the medicine, but when raised under its corseted manners, it’s whiplash-inducing to make the sharp turn from intellectual parlance to wild grit before we’re ready. This is where I see Monster Romances as both catalysts and guides.

These monster romance stories work because they live under the radar of rational culture, in the place where thousands of readers meet their monsters in private and (re)learn the wisdom of their bodies’ arousal, voracious appetite and desires.

Even if at first, this is all taking place in our imaginations, populating our fantasies, we learn through the monster how to understand the other (inner and outer), by taking them in through the body’s honest doors: skin, mouth, sex. The places where you can’t fake your response.

Little Mermaid (circa 1923) - Edmund Dulac

My lifeline this year hasn’t been the language of therapy, heady self-help theories, or even the sublimation of spirituality. It’s been story after story of women who enter the cave and find something waiting that sees them completely—grieving, raging, ravenous, and lustful—and doesn’t step back. Instead, finds them more delicious—riper—for their jagged edges, their feral grief, their untamed wanting. The monster’s devotion says this: “I see your claws and raise you mine.”

We’re not reading for the endings at all. We’re reading for the devouring. We’re reading them because they know something our culture has forgotten: that resurrection happens through appetite, not abstinence.

That the way back to life might look like letting yourself be devoured by something that’s been waiting in your own depths, hungry and patient, but completely uninterested in your purifying salvation.

So here’s my confession: the monsters brought me back to life. Not by fixing me, but by showing me that some hungers will bite if not fed. That wanting something with an appetite as big as mine, something that won’t blink at my whole self—the good, the bad, and the ugly—isn’t pathology. It’s recognition.

The tooth-and-claw pulse of monstrous devotion refuses to make desire polite. It knows wildness should be worshipped, that tenderness can draw blood, that feeding mutual hunger is how we stay alive. It knows that we don’t need another story about healing with its constant hammering that we’re broken and in need to be fixed and made better.

We need stories about appetite. About what happens when two hungers meet in the dark and decide to feast instead of flee.

Simpatia (La rabia del gato) (1955) - Remedios Varo

This is why monster romance isn’t a passing fad but an archetypal eruption.

Under the radar of respectability, dismissed as escapist fantasy and smut-filled fluff, a collective healing is happening: through stories that know vitality comes from arousal itself—not the idea of it, but the actual thrumming between our legs. Each reader who meets their monster in the imaginal realm and learns they too have fangs is feeding something larger—a cultural counterspell to centuries of being told our hungers are shameful, our desires dangerous, and our bodies problems to be solved.

But here’s what I’m starting to understand: these aren’t just stories. Each time a reader’s arousal meets a monster’s hunger on the page, something moves in the collective unconscious.

The archetypes themselves have always been awake, using our thrumming bodies as portals back into the world. We think we’re reading for escape, but we’re actually opening doorways—one orgasm, one bite, one recognition at a time. The monsters aren’t here to heal us. They’re here to feed, to mate with our consciousness, to tear new holes in a reality that’s gotten too numb for anything wild to survive.

This isn’t a visit—it’s a jailbreak, and every reader who throbs in response becomes part of the escape route.

May the Power of Fluff be with you.

Vanessa Couto